The carbon embodied in buildings contributes to climate change. Nicole Sullivan, our Head of Strategy and Impact Australia, and Tori Wouters, our Sustainability and Systems Specialist, discuss the problem and actions underway in construction industries in Australia and New Zealand.

Please tell us about embodied carbon.

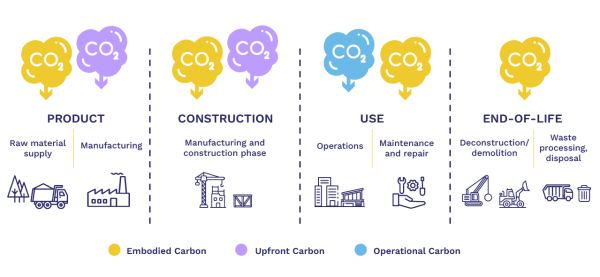

Nicole – It’s the emissions related to a product across its life cycle. For a building, this includes the emissions from the materials and products the building is made of, the construction process itself, disposing of construction waste, maintaining and refurbishing the building, and disposing of the building at the end of its life. For example, in a building project, embodied carbon might come from producing materials like steel, concrete and glass, and from the fuel needed to power an excavator making holes in the ground.

Why is embodied carbon a problem and how does it relate to climate change?

Nicole – Buildings and their life cycle make up 39% of carbon emissions from energy. Embodied carbon is a big percentage of that.

There is also operational carbon: the emissions from heating and cooling a building. Using renewable energy reduces operational carbon, but lowering the carbon embodied in the building is more challenging.

With an increasing population, there will also be more buildings. We need to build smart so that buildings and infrastructure, and the emissions they embody, last as long as possible.

How can we reduce embodied carbon?

Tori – All industries need to convert their power consumption to renewables as much as they can, as quickly as they can. While emissions from some industrial processes are hard to reduce, switching to renewable electricity is important.

We also need more consistent, verified data. The National Australian Built Environment Rating System (NABERS) is developing a rating tool for the industry to use to measure embodied carbon. Groups like the Green Building Council of Australia (GBCA) support this. The GBCA intends to follow the method NABERS develops in tools like Green Star Buildings.

In New Zealand, our team developed an Embodied Carbon Calculator with the New Zealand Green Building Council (NZGBC). This gives a consistent way to measure and report embodied carbon.

That consistency creates competition to drive down emissions. This applies to manufacturers, developers and planners. For example, if a developer can accurately measure the embodied carbon in a building, they can then work to reduce the amount.

What does the building industry need to reduce embodied carbon?

Nicole – They need good data. And we need to educate the industry so their decisions are data-based and they can adopt new approaches.

We need to think about the products and how they are used. For example, we could reuse building elements such as cross-laminated timber (CLT), laminated veneer lumber or steel beams if we know their exact specifications and strength. Building Material Passports can give that information. We’re not yet pulling down modern buildings, but major structures using CLT or steel sections seem to have good circular opportunities at the end of life. This preserves the invested and locked-away carbon and avoids the need to create new materials.

We need our whole value chain to learn about different approaches. For example, building designers can use tapered steel beams that are strong in the places they need to be and use less steel where it’s not needed.

There are also possibilities of replacing up to 70% of cement in concrete. Trades will learn to handle the pour of different concrete types, and how to manage schedules to achieve the desired strength. Thinking differently reduces emissions.

Nicole Sullivan and Tori Wouters

How can manufacturers and associations help lower embodied carbon?

Nicole – Manufacturers can provide data on their product’s emissions in Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs). Then they can work to reduce those emissions by using as much renewable energy as they can and investing in new lower carbon technologies.

Industry bodies have important roles. We work with associations to help them support their industry, particularly the smaller businesses.

Tori – The Australian Steel Institute (ASI)’s Sustainable Steel Australia (SSA) program is a good example. ASI saw what industry was asking of its members and developed a standard to help them deliver. We worked with the ASI to develop the SSA standard to agree with the GBCA’s updated Responsible Products Framework (currently in development).

What are national and state governments doing to lower embodied carbon?

Nicole – In New Zealand the Ministry for Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) launched the Building for Climate Change programme which will reduce embodied carbon toward New Zealand’s 2050 net zero carbon goal.

The Australian National Construction Code (NCC) needs to mandate measuring and then reducing embodied carbon. I'd love to see it in the 2025 NCC, but 2028 is likely more realistic.

The New South Wales State Environmental Planning Policy (SEPP) for Sustainable Buildings requires reporting of embodied carbon. I expect other states to follow.

Governments in both countries need to develop more renewable energy sources that lowers embodied carbon when products are manufactured.

How can we rethink how we use buildings to lower embodied carbon?

Nicole – The building with the lowest embodied carbon is the one not built. Using lower-carbon products is important but it shouldn’t be the first option.

We need to reuse or repurpose spaces more often. One building with different users during the day and night is better than two buildings.

Using circular thinking can reduce embodied carbon too. When refurbishing a building, wall linings are rarely reused or recycled. Landfilling these wastes the products and the carbon embodied in them.

24 July 2023