This blog is the third in a series – read about renewable energy and decarbonising transport.

The New Zealand building sector is currently facing pressure from many directions. We are a country with high living and building costs. We are in the middle of a housing crisis and a building boom. Like many other countries, we’re struggling with supply. But we must urgently change how we build so we can move towards a zero-carbon future. In this ‘moving faster’ blog, thinkstep-anz Technical Director Jeff Vickers argues that manufacturers need to offer lower-carbon options, specifiers need to choose them, and architects need to optimise design and available materials.

The Emission Reduction Plan’s long-term vision is that by 2050 Aotearoa New Zealand’s building-related emissions are near zero and buildings provide healthy places to work and live for present and future generations. Buildings are estimated to be responsible for producing around 10 percent of national greenhouse gas emissions. When we are talking about carbon in the built environment, there are two different kinds: operational and embodied carbon.

Operational carbon

Operational carbon stems from heating, cooling and lighting a building, as well as all electric devices. It is visible to a building’s occupant through their power bills and can change as we decarbonise our grid and undertake energy saving efforts.

To tackle operational carbon, the Government released an update to the Building Code’s H1 Energy Efficiency measures in November 2021. By strengthening the requirements for insulation and energy efficiency, we can make sure we build healthy homes that are cheaper to heat and cool. As most of our heating is powered by electricity from New Zealand’s already predominantly renewable grid, we’re on a reasonable trajectory to reach our goals for operational carbon.

Embodied carbon

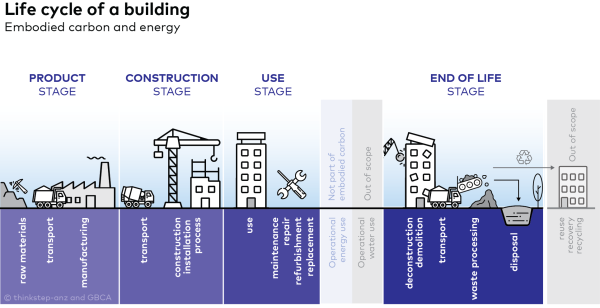

Embodied carbon represents the greenhouse gas emissions that are associated with producing the materials we use to build, the construction process, and the building’s eventual demolition. It is less obvious to the occupants and is largely locked in before a building is used. These additional emissions are accounted for in the energy, industry, waste and transport sectors within New Zealand’s Greenhouse Gas Inventory.

Supply and demand need to work together

New Zealand is currently experiencing a building boom but we’re still largely building as we always have without putting enough thought into decarbonising our building stock.

To reduce the embodied carbon in buildings, suppliers need to have low-carbon building products available, and these then need to get specified and used in construction. Lower carbon can mean choosing wood, but it can also mean low-carbon concrete, low-carbon steel or low-carbon aluminium. Put another way, we need the supply side and the demand side working together.

The New Zealand Government’s approach

Under the Government’s proposed Building for Climate Change (BfCC) programme, prospective homeowners, builders, architects and designers will need to not only worry about the size and the price of a new dwelling but also look at the embodied carbon it emits.

They will need to ask the questions:

- How can we choose the lowest carbon materials?

- How can we reduce waste?

- How can we extend the life of older buildings while also providing good thermal performance?

- And lastly, but equally importantly: How can we do this without it costing too much?

The proposed BfCC programme would include whole-of-life carbon reporting as part of the building consent process. If accepted, building plans would need carbon measurements from the extraction of the raw materials to the demolition of the building. The mandatory embodied carbon reporting would kick off in 2024 and sinking caps in line with a shrinking national carbon budget would be introduced from 2025.

Our thinkstep-anz findings

In 2019 the thinkstep-anz report Under construction identified opportunities to decarbonise New Zealand’s building and construction sector by 40% with a focus on embodied emissions from now until 2050.

We found that, at the national level, the carbon footprint of new-build construction and renovation was calculated to emit at least 2,900 kt of CO2-equivalent (CO2e) per year – equivalent to more than 1 million passenger cars on New Zealand’s roads.

The strategies set out in the report could save approximately 1,200 kt CO2e per year: that’s as much as taking 460,000 passenger cars off the road permanently.

The main contributors to embodied emissions

The key materials contributing to embodied emissions in New Zealand were found to be steel and concrete, which together contribute more than 50% of the carbon footprint of both residential and non-residential construction (excluding fit-out and building services). Aluminium was also very significant for non-residential construction. For residential construction, timber framing was the next biggest contributor, followed by paint, aluminium and plasterboard.

The roles of suppliers, specifiers and customers

It is not only material suppliers who need to implement low-carbon manufacturing technologies, but also specifiers who need to consciously choose those materials and customers who need to demand low-carbon homes. There are already many options on the market. A recent study we conducted for MBIE found that by optimising designs and picking the right products, significant decarbonising was already possible without any additional cost.

With material manufacturers doing their bit by developing lower-carbon options and architects choosing the optimal design and the optimal materials, there is a potential to reduce embodied carbon by even more than 40%. There’s no time to lose to start building for our low-carbon future.

Suppliers and customers both have important roles to play

Supply-side strategies include:

- Energy efficiency and material efficiency projects

- Designing and supplying lightweight products

- Stopping process emissions from reaching the atmosphere (carbon capture and storage)

- Decarbonising electricity grids through increased use of renewables

- Substituting thermal energy (e.g. replacement of coal with natural gas, natural gas with biogas, or natural gas with biomass)

Demand-side strategies include:

- Designing to optimise material use and avoid generating waste

- Encouraging the use of rating tools like Green Star which specifically target reductions in upfront carbon emissions

- Substituting materials (i.e. substituting a higher-impact material for a lower-impact material that serves the same function)

- Designing buildings for multi-functionality so that fewer buildings are needed overall

- Prolonging the life of existing buildings through proper maintenance and renovation

- Recycling and upcycling of materials from decommissioned buildings

June 2022