Understanding the environmental impact of a product and its packaging is one of the reasons clients commonly call on us at thinkstep-anz. By measuring this impact and providing them with robust data, we can help our clients make science-based decisions and communicate with their stakeholders confidently and credibly.

Challenge your intuition!

No one can know the real environmental impact of their product until they examine it in detail, using indicators such as carbon footprint and energy demands. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) lets you do this by looking at the environmental impact over your product's entire life cycle.

Be prepared for surprising findings

The results of LCA studies can be unexpected and at odds with our intuition (another good reason to do an LCA!) Here are a couple of examples involving packaging LCAs.

Example 1: New Zealand Post’s courier bags

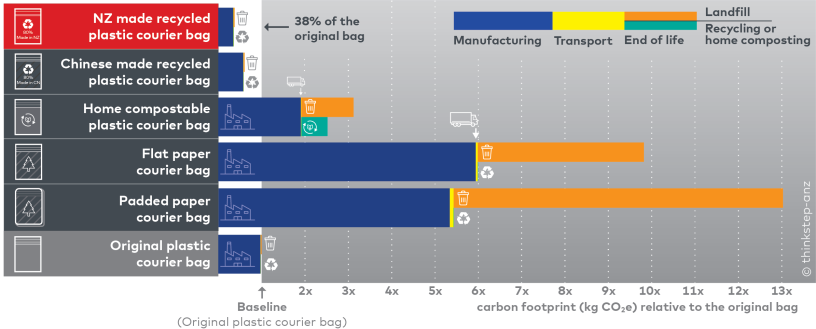

New Zealand Post wanted to offer their customers a more ‘environmentally-friendly’ courier bag. They commissioned us to carry out a comparative LCA. Our study compared the original A5 courier bag made from virgin LDPE (low-density polyethylene) with five alternatives, which included paper and home-compostable bags. We assessed the bags’ carbon footprints, as well as their wider environmental impacts, using 15 indicators.

The surprise discovery? New Zealand Post learned that the most sustainable packaging for their courier bags is made in New Zealand from 80 percent recycled LDPE plastic.

The recycled LDPE bag significantly outperformed all other options we considered in our peer-reviewed study. In fact, the carbon emissions from the recycled bag were fewer than half the emissions the original courier bag produced — a reduction of 191 t CO2e a year.

‘It's certainly a surprise to a lot of people, me included, just how much the recycled plastic courier bag was beneficial over the other options considered,’ said Sam Bridgman, former Senior Environment Specialist at New Zealand Post.

On the flipside, paper bags, which many think are environmentally preferable, performed the worst. When all bags were landfilled at end-of-life, the carbon footprint of the flat paper bag was nearly ten times greater than the footprint of the original courier bag. The padded bag (including shredded paper for protection) had a carbon footprint 13 times higher. Even if the flat paper bag was recycled, its carbon footprint was six times higher than the footprint of the original bag.

Why did paper bags perform worse than plastic in the New Zealand Post study? For two main reasons. First, paper is a lot heavier than plastic. More material is needed to package the same amount of product to keep it safe. Secondly, the paper bags considered in the study are made in Australia and would need to be imported to New Zealand. In comparison, the lightweight, recycled bags are made in New Zealand using electricity, 84% of which is renewable.

And the compostable bags? Although they’re made from starch, they contain a binding agent derived from oil. Carbon dioxide and methane are released when the bags are composted. Our LCA study found the carbon footprint of the compostable bag was more than double that of the original bag.

‘That's not to say that compostables can't be a good solution', says Jeff Vickers, thinkstep-anz’s Technical Director. ‘In many cases they’re good if there's a risk of them ending up in the wider environment, say as litter. But in the case of a courier bag, this isn't usually the case.’

Example 2: Tetra Pak’s cartons

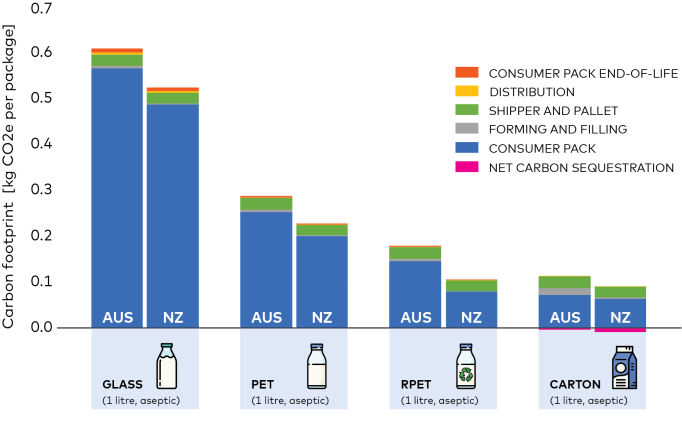

In another LCA study, we worked with Tetra Pak to compare the impact of their cartons with eight other packaging materials, such as glass and PET bottles.

The surprise discovery? The results showed that cartons have the lowest carbon footprint of all packaging systems considered – across all size classes and product categories.

The cartons’ light weight is part of the reason for this, as well as the relatively low impact of paperboard per kilogram. Another reason is that, when cartons are disposed of in landfill, they may only partly release the carbon sequestered when the trees were growing. This means that the cartons can be net sequesters of carbon: the emissions (methane and carbon dioxide) released when the paperboard decomposes in landfill are lower than the amount of carbon stored in the paper.

What these two case studies teach us

You can use LCA to:

1. Understand the big picture and the true environmental impact

LCA studies help companies to understand their impacts and take responsibility for them.

The outcomes of these LCA studies remind us why it’s worthwhile to test our assumptions and assess the impacts of products from ‘cradle to grave’. Jeff Vickers emphasises how important it is to compare based on facts rather than feelings.

‘People focus on what they control but they forget about the upstream supply chain or the downstream customer chain, which can have a huge impact.'

2. Discover the right solutions for your business

We need to reduce our reliance on single-use plastics. However, as Jeff explains, the real concern is when plastics get into the natural environment. In the case of courier bags, there is little risk of them ending up as litter because they are carried from door-to-door.

‘From the perspective of many other environmental indicators, [this study shows] that plastic is a lightweight solution to a problem. The key thing is not getting it into the environment in the first place.’

3. Combat greenwashing

Consumer pressure to offer paper or compostable options is one of the reasons New Zealand Post approached us to carry out their study. By assessing all the options and showing how they came to their decision, NZ Post can contribute to discussions about what defines a ‘green product’. Our LCA made this possible by examining the impact of the bags across their whole lifecycle.

As Sam Bridgeman says, ‘Only by comparing across the full lifecycle could we really understand the impact.’

4. Counter prejudice against packaging in general (and plastic in particular)

Equipped with reliable data, New Zealand Post could make decisions based on science. They could justify why they were not responding to customer demand to use an alternative to plastic.

In our webinar with Tetra Pak, Jeff noted how we often assume a product’s waste phase has the greatest environmental impact and overlook the impact of manufacturing.

'This study shows that a lot of the impact of a packaging format comes from actually making the stuff. People want to deal with waste because it's in their hand… But probably more important is how the packaging was made in the first place.’

5. Tell your brand story

Beyond crunching the numbers and interpreting the data, LCA studies open up opportunities to talk with your customers and stakeholders. When you're telling them your ‘brand story’, explain the steps you're taking to make your product more sustainable.

As Tetra Pak’s Marketing Director Jaymie Pagdato explains, ‘There's an ever-growing awareness and need for education among consumers, and it will just continue. An LCA can give [brand owners] an opportunity to talk about the package and the life that the cartons go through before they reach consumers.’

April 2022